Ultra-Local, Full-Circle Self-Sufficiency

The Significance of a Self-Sufficiency Garden Food System

Imagine for a moment that we could ramp up a self-sufficiency garden system enough to provide 50% of the U.S. population with healthy, balanced diets. How would that play out on a national scale, over time? Here we’ll ponder the significance of ten likely outcomes.

Setting a compelling example

Given America’s status as the leading exponent of industrial food, moving to 50% garden fare would set a startling example for the rest of the world. That is, assuming that the rest of the world doesn’t get there before we do. Russia has already done it, but shh, that’s a glorious secret.1 Already, the percent of the world’s food produced by the industrial model is estimated to be as low as 30 percent, depending on which studies you believe2,3. That would mean the other 70% is fed by small-holders, home gardens, and non-commercial hunting, gathering, and fishing. If, as some reports claim (based on production, not consumption)4,5, global industrial is a good bit higher than 30%, having the U.S. lead with gardens would be even more significant and inspiring for other countries.

Balanced diets, not UPFs

Huge positive here. As I’ve noted repeatedly, UPFs constitute 75% of the American diet and 60% of its consumed calories. Industrial manipulation and nutrition reduction render them pretty much the extreme opposite of a balanced diet. A meal from a self-sufficiency garden couldn’t be more different. Not only does it lack UPFs, it’s also nutritionally balanced, outdoing even most ordinary gardens that emphasize watery vegetables low in protein and energy. As little as half of the country switching from UPFs to ULFs (ultra-local foods) would be enormously significant for the nation’s health.

Jobs: losses offset by gains

No doubt about it, a substantial switch to garden food would result in a loss of many jobs, and not only at the farm. It takes thousands of people to support the industrial food infrastructure, from mining and refining ag-related fossil fuels and hardware; to designing, building, and maintaining the required factories and machinery; to transporting structural components and food by ground, sea, and air; to educating workers at all levels. Contrary to media claims, the average farmer does not feed a hundred people. Rather, most of the work is done off the farm by the sprawling infrastructure support team. Besides, AI will be removing many of those jobs well before gardens could get around to it. The industrial food system has no problem with that, as it’s already cranking up blockchains and robotics, from “smart” ag tech at one end to self-checkout stations at the other.

Altogether, increasing the proportion of the nation’s food coming from gardens will shake up all parts of the industrial system. But because of the industry’s deeply-entrenched problems, that will have to happen sooner or later even without gardens, and probably sooner now that climate change is swiftly moving up the goal posts. In any case, a major shift in production methodology typically generates a shift in jobs from the older to the newer way of doing things. Here, think of a garden support system creating new companies and jobs to provide compost, mulch, greenhouses, gardening supplies and equipment, coaching and education, and done-for-you gardening services.

Grocery stores losing business

In view of the meager 1-3% profit margin of U.S. supermarkets, a switch to garden-supplied food would bankrupt grocers long before a 50% mark is reached. For every 1% increase in garden fare, people would buy 1% less at grocery stores, which would then have to compensate with increased prices. Shoppers who could afford to would grudgingly pay—up to a point—but those who couldn’t, wouldn’t. So would those priced out of the supermarket be the first to take up gardening? Not necessarily; surveys show that wealthier people are consistently among the first, not the last, to take up vegetable gardening. But no matter who starts first, grocers will face a day of reckoning once the gardening train really takes off.

This harks back to the previous post, where we considered what it would take to convince people that gardens could be more convenient than supermarkets. There, I said only environmental disasters would change most minds. But depending on how fast gardening ticks up, and how soon and seriously it bites into grocery store profits, it could well be the higher cost of food that does it instead. Already, food prices are rising ominously even without pressure from gardens.

Farmers also losing out?

At the other end of the industrial profit stream (with Big Ag and Big Food hoovering up the lion’s share in between) is the farmers. The largest farms realize the greatest margins and the smallest ones the least, but the average is around 11%, of which subsidies account for about 20% of the profit. You’d think that would make farmers better prepared for an increased supply of garden food, but because of looming tariffs and the loss of many federal ag supports, farm interests are already angling for another big Trump-delivered subsidy bailout. Trouble is, this one would have to be much larger than his last one—making it a harder sell for deficit hawks. What’s more, other governments are already looking to diversify their food imports away from the U.S. because of its diminishing trade credibility. The future is not exactly rosy for farmers, gardens or no.

Significant pushback?

Of course, we can expect that the multi-national ag and food corporations, wealthy land-owners, and global food speculators would be none too pleased to lose even a small percentage of market share to gardeners. But not to worry. They’re deeply convinced that backyard gardens are way too wimpy to compete with the well-entrenched juggernaut. So they won’t respond to any significant degree—whether to garden buildup or climate change breakdown—until it’s too late to have much effect.

UPFs: scarier than gardens?

Which, by the way, calls for a re-visit to ultra-processed foods, this time from Marion Nestle, the renowned nutritionist critic of the food industry. She says it’s facing four big threats to the market dominance of UPFs: public interest in the negative health effects; GLP-1 drugs (e.g., Wegovy) that make people not want to eat them; inflation; and HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr’s efforts to get them out of the food supply6. According to her, the industry sees a perilous handwriting on the wall with the perfect storm of these four elements coming together. So if—contrary to my read—the juggernaut is already spooked, the decline of UPFs could eclipse gardens and climate as the leading cause of industry shakeup and job loss.

Natural resource windfalls

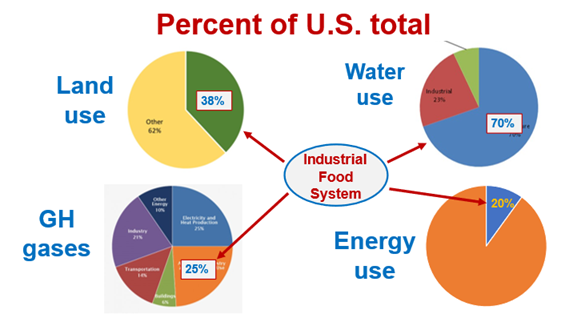

If job losses sound like a downside, a transition to 50% garden food will have enormous upsides that will more than counter them. In addition to new jobs, it would free up boatloads of natural resources that are currently either stressed or in short supply. Estimates vary, but about 40% of the land, 70% of the water, and 20% of the energy we use is gobbled up by agriculture. In addition, the industrial food system is responsible for at least 25% of on-site greenhouse emissions. The total is more like 40% if you count emissions generated from infrastructure buildout, maintenance, and on-the-ground effects of exploitative financing that keep it all running.

Now, remember the table summarizing the increased efficiency—by orders of magnitude—of a garden-based food system compared to the industrial system? If you don’t, here it is again:

If just half of these quantum leaps in efficiency were realized, it would leverage a huge lift to an economy and food system beset by many challenges. More specifically, if the decrease in food footprint from industrial’s 3.0 acres to garden’s 0.03 is any indication, it would generate similar reductions in water and energy use, even if applied to only half of food production. It would also substantially reduce greenhouse emissions. The most significant impact by far, however, would be decreasing external costs from $trillions to virtually zero.

The significance of industry cluelessness

So far, champions of industrial food have shown very little awareness of just how significant improved efficiency could be. I often see exaggerated reports of the way regenerative agriculture will revolutionize industrial food7. Or how this or that scientific breakthrough could generate a 15% increase in crop yields or game-changing resistance to ever-hotter weather. Or how various lab-generated food-goos will transform our food supply, and how wonderful those goos would be. Never mind that it would take massive research, development, and infrastructure investment over many years to commercialize such increases and structural buildouts at scale. Which (for higher yields) we don’t need anyway since global hunger is due to inadequate food distribution, not lack of quantity.

But suppose the goal was to use less land rather than to feed more people. And suppose that we somehow did achieve a 15% increase in yield across all of the nation’s vast crop and pasture lands, enabling us to produce the same amount of food on 15% less area. The U.S. has a billion acres in agricultural land, 15% of which would be 150 million. Sounds impressive, but by contrast, switching from the industrial system to self-sufficiency gardens would reduce ag land use from 3.0 to 0.03 acres per person. That would thus free up 99% of the total amount of ag land—990 million acres. That’s 6.6 times as much as 150 million.

Yet it’s certainly not as though the whole country is going to transition to garden-based food; I’d settle for just half of that, as I indicated all along. That would leave “only” 495 million acres of freed-up land, still over three times as much as a 15% yield increase would deliver. If it could. But it can’t, because scaling up commercial yields by 15% over a billion acres of crop and pasture lands would be an unbelievably herculean task that simply has no chance of happening any time soon, if ever. Yes, I’m aware that yields of corn, wheat, and soy increased by a good bit more than that from 2000 to 2019. However, those crops account for less than a quarter of all ag land, and have seen virtually no growth in yield over the past five years.

Overall, the significance of this thought experiment is the revelation that it’s much more effective to move to a garden system than to hope that theoretical yield increases will pan out. Especially given how little time we have to prepare for increasingly frequent environmental disasters.

Is the scope of all this still a little hard to grasp? Here is an overview of the main physical consequences of the described transitions, summarized in two graphics.

These graphs frame just some of the significance that would result from ramping up to half of our food from gardens. They don’t even get into the specifics of the economic and social benefits. Nor do they broach in more detail the implications of preparing us for climate disasters much more effectively than the industrial system can. That will come in in the next two posts.

A rising tide of relief

And finally, there’s the not-to-be-underestimated significance of relief. Recall that over time, for every self-sufficiency garden established and used as the primary source of food for one person, three acres of industrial ag land will be freed up. This would gradually swell to thousands, then millions, then hundreds of millions of acres. What would become of all that land? Would it all be “re-wilded”, as some call for? Made into parks? Re-populated by people fleeing overcrowded cities? Recall (again, can’t emphasize it enough) that the industrial food system incurs trillions of dollars worth of externalized damage every year, a toll that will diminish in proportion to the number of gardens adopted. How will all that money be re-distributed as it becomes available?

It's easy to lose sight of, but industrial agriculture is basically a chemical and physical assault on the land, especially against soil and pests. During the nine years I engaged in potato breeding research, I often noticed industry language that invoked “the battle of the beetle” or farmers getting “hammered” by aphids, or “total war” against this or that disease. For many years, commercial ag has used ever-heavier tools to demolish natural “invaders”, and just as regularly, nature has fought back, developing resistance or work-arounds to whatever artillery was thrown against it. Back and forth it’s gone, decade after decade. And that’s just one consequence of the industry’s machine-like, domination-of-nature attitude. What will be the response once the siege is lifted, even partially? For starters, I see the land and the people collectively breathing a huge sigh of relief. The practical details of how it all plays out in nature and our national life remain to be seen. Stay tuned.

1Sharashkin, L. 2008. The socioeconomic and cultural significance of food gardening in the Vladimir region of Russia. PhD dissertation, University of Missouri. https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/handle/10355/5568

2Who will feed us? 2017. The industrial food chain vs. the peasant food web. Etc. Group, 3rd ed.

3Small-scale farmers still feed the world. (PDF). chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.etcgroup.org/files/files/31-01-2022_small-scale_farmers_and_peasants_still_feed_the_world.pdf

4Riciarrdi, V., et al. 2018. How much of our world’s food do smallholders produce? Global Food Security. 17: 64-72. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325405959_How_much_of_the_world's_food_do_smallholders_produce?

5Louder, S.K., et al. 2021. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? World Development. 142.

6Maldarelli, C. 2025. “To me, it’s junk food.” Inverse. https://www.inverse.com/health/marion-nestle-interview-ultraprocessed-food-health

7Torella, K. 2025. The false climate solution that just won’t die. Vox. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/409940/regenerative-agriculture-kiss-the-ground-common-ground