Ultra-Local, Full-Circle Self-Sufficiency

ULFs (Ultra-Local Foods), Not Regenerative Ag, Are the Answer to Industrial Food

I can’t tell you the number of glowing accounts I’ve heard and seen about regenerative agriculture over the last few years. And it’s no wonder why. Guided by ecological principles, it promotes “regenerating” healthy soil to increase organic matter, water retention, fertility, and carbon sequestration. The hope is to foster more resilient outcomes for cropland and livestock operations, as well as healthier food and a more sustainable environment. All in service of reversing the soil degradation—and the dreadful downstream damage—that characterizes industrial agriculture.

Make no mistake, if farms were to adopt this practice, it would indeed be a boon all around. Yet in the context of the food system it serves and ultimately depends on, a closer look reveals that it just hasn’t been thought through very well. Want to know why? Read on.

Too limited

Regenerative agriculture is nothing new. It and similar sustainable ag concepts have been around since the early days of the organic movement decades ago. But admirable as these eco-efforts truly are, they have never produced more than about 1 percent of wholesale food sales in the U.S. Yes, organic is now at 6 percent of wholesale, but 35 years have passed since the USDA launched the organic label, and much of the targeted market has been subsumed by the industry, so we now have industrial organic. Regenerative ag, like organic, “…fails to tackle systemic social and political issues. As a result, the movement may perpetuate business-as-usual in the food system, rather than transform it.”1 That’s not to say that reduction of harmful synthetic chemicals hasn’t been good. It has—but only in a small percentage of our food.

Too pricey

Organic food costs an average of 47% more than non-organic2, and although I haven’t seen any estimates for regenerative, one ardent proponent told me to expect a 20-30% premium. Regenerative ag includes many of the same protocols as organic, so it, too will incur additional costs. While some (including me) are willing to pay the difference, it prevents regenerative from giving conventional a run for its money. Industry externalizes about two-thirds of its costs, which regenerative ag can’t replicate, so it has no choice but to slide the added cost of revitalizing soil down the food chain to the mom pushing the grocery cart. But it’s evidently too much to ask of most people. Especially now, when food prices are increasing faster than the overall rate of inflation. (Don’t even ask about eggs.)

I’ve seen regenerative advocates argue that it can match or surpass conventional yields or revenues per unit of yield and is therefore scalable. However, making the same kinds of claims, organic has shown that those metrics don’t usually translate to the shopping cart. Hence the 47% premium. This is just one result of not looking at the system as a whole when assessing regenerative.

Too dependent on subsidies to massively scale

Strategies, reports, predictions, and schemes abound as to how regenerative ag can, could, would, promises, or hopes to scale to major relevance—but only with the help of subsidies. Yet ag subsidies almost always morph into dependency. Thus one idea is to simply move industrial entitlements over to regenerative. Says regenerative farmer Patrick Holden of Wales, “. . . industrialized, intensive systems pay better—what’s needed are redirected subsidies to ensure farming and nature can coexist in a field . . .”3 Ironically, this would allow regenerative to externalize a portion of its true costs, just as the industry does. Not only would that throw up another barrier to regenerative becoming a major player in the food market, it would also increase an existing economic burden on the taxpayer if it did somehow manage to go big-time. There are only so many subsidy dollars to go around, and the industry will surely fight to keep the lion’s share of ag freebies for itself. Especially now, with federal aids to agriculture in a state of chaos.

Too unable to address downstream problems, especially UPFs

Most proponents of regenerative ag seem to be unaware that it addresses only the initial, production stage of the 1,500 mile-long industrial food stream. They assume that if they just fix that front edge, it will magically solve all food system problems, as the documentary “Kiss the Ground” would so misleadingly like you to believe4. That is, they ignore the downstream problems, especially UPFs, by far the most damaging consequence of the industrial system. Regenerative ag does nothing to address them. Feeding responsibly farmed foodstuffs into UPFs will render them just as unhealthy as sources from industrial ag. Big corporations like WalMart, Nestle, McCain, PepsiCo, and others know this, which is why they’ve committed—at least on paper—to adopting regenerative ag while continuing to churn out all the UPFs they want. That way, they get the green creds, though it remains to be seen whether they can avoid price increases if they live up to their promises. In other words, their green is washed, although I think in some cases they actually believe that regenerative will improve their UPFs. As we saw at length in the last post, it won’t.

Too scary

The average age of U.S. farmers is 58. With a few laudable exceptions, most of them are too conservative and/or too old and set in their ways to venture more than a modest step toward regenerative ag. But as Holden says, you have to consider what they’re up against: a system that in many ways holds them hostage “. . . with most farmers operating on wafer-thin margins, embattled by climate change and demands for cheap food, and the victims of price shocks passed down the supply chain, [so that] the transition remains unpalatable, or simply unfeasible, for many.”3 The result: just not anywhere near enough “boots on the ground” to leverage a major shift to sustainable food production.

Too slow

Even if younger, more open-minded farmers started to massively adopt regenerative ag tomorrow, it would be too late to have a decisive impact on food production any time soon. Consider just one example of why: the pace of soil erosion. About half of U.S. farm topsoil has been washed or blown away, and the remaining half has lost 50% of its organic matter. Despite recently decreasing rates of erosion, soil is still being lost 10-17 times as fast as it’s being replaced. Regenerating it back to its former depth and organic matter content is a truly enormous, time-consuming task. It will take at least a couple generations to reverse deeply unsustainable ways of thinking and farming at the current rate of food system wakeup. As you will see in the next angle of the challenge.

Too late

Industry rep Barry Parkin, chief procurement and sustainability officer at pet food and candy-maker Mars, holds that regen ag methods “. . . have been adopted across about 12% of farmland . . .” He’s undoubtably referring to quick initial steps like cover crops and no-plow, for sure not the full restoration of soil depth and organic matter. According to Dr Kristine Nichols, a soil microbiologist and regenerative agriculture expert, only about 1.5% of U.S. farmland is being farmed regeneratively.5 This figure is more in line with a practice still struggling to gain a toehold in the farming scene. But Parkin is right when he says that it’s being adopted “. . . at less than 1% a year. Clearly, we don’t have 50 years or more for this to roll out.”6

Lurking behind that dire prognosis are the climate change disasters that loom over not just farming but everything else as well. And they’re arriving more and more intensely and frequently. The floods in western N.C. following Helene and the fires in LA the are the most recent examples as of this writing, but they’re by no means isolated. Between 1980 and 2019 there were an average of 10 billion-dollar-plus disasters a year, whereas the average from 2020-2024 was 23 per year.7 These events are accelerating far too quickly for regenerative ag—at 1% of food sales and 1.5% of current farmland, increasing at 1% a year—to effectively address climate change before it’s too late. That is, if the 35 years it took to reach 6% certified organic is any indication.

Too weak

Even if all seven of the other “Toos” could be successfully resolved, regenerative ag, with its one percents, is just too effete to repair the mighty industrial food system. Big Ag—and its extension, Big Food—are just too colossal, too corrupt, and too deeply dug in. Attempting to improve it to any significant degree—e.g., by installing the mostly ignored stopgaps in Mark Hyman’s Food Fix8—would be like trying to rearrange a cemetery. Tomorrow.

Much more worthwhile would be to adopt the approach of Buckminster Fuller: "You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete."

Regenerative ag, which itself is often portrayed as that new model, is not only not new, it’s not up to the job, as we’ve just seen. We need a much more effective and nimble model, with compellingly greater leverage on all fronts. That’s what a self-sufficiency garden system would be. And as a result, it would accomplish so much more, so much faster.

ULFs – the Key to a Self-Sufficiency Garden Food System

Compared to farms, self-sufficiency gardens are just a distinctly different proposition, which is why I’ve devoted five previous posts to helping people get accustomed to the idea. In fact, they’re so different that even regenerative ag farms don’t match up with them very well. The following observations add a critical step to illustrating why. So here we go.

Able to scale massively

Like regenerative ag, home gardens currently account for only about 1% the U.S. food supply. However, that’s measured in calories, and as we saw in a previous post, American gardens typically focus almost entirely on watery vegetables low in protein and calories, so the low figure is probably accurate. Measured as a percent of cash value, home-grown vegetables account for more like 10% of our diet (see below). That’s with the 41 percent of U.S. households that already have a food garden of some kind. Transformed into self-sufficiency gardens, the percent of calories in the home-grown diet would rise accordingly. Plus, they would provide a balanced diet, which the average current garden falls well short of.

A robust contribution of household gardens to the food supply, as I keep repeating from Sharashkin’s study, has already been accomplished in Russia9. Fifty percent of its food comes from its “secret” household gardens, which do include plenty of foods high in protein and calories, especially from potatoes. Moreover, Sharashkin has shown that the economic, social, and cultural benefits of household gardens are much more extensive than anything regenerative ag, with its 1% delivery metrics, has thus far been able to demonstrate. If Russia can achieve all that, with fewer resources and a less conducive climate than we have, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t be able to do even better.

Yet as also noted previously, we, too have shown the potential to ramp up home-grown productivity with victory gardens, and quickly. As have other countries. That speed-to-scale metric will come in handy once the frequency and intensity of climate change disasters start overwhelming the industrial system’s ability to restock grocery stores promptly. And that perilous time may come sooner than you think. Following Helene, it took weeks to get many of the supermarkets in Asheville, N.C. and vicinity back into full operation. In the meantime, everything from military helicopters dropping pallets of MREs (meals ready to eat) to pack mules were used to get food to people who couldn’t afford to just leave the area for a while. Through how many catastrophes could that continue, once they start to happen closer together?

Cost-efficient

Saving money is not the number one reason gardeners grow their own food (taste is). However, even the typically small (20’x30’) American garden generates an average $677 worth of fruits and vegetables beyond the $238 spent on materials and supplies10. My (35’x40’) 2021 self-sufficiency garden yielded a gross value of $3,727 from over 1,000 pounds of vegetables—a year’s worth of a balanced diet. And neither of those measures assigns a cash value to the exercise, connection to nature, and other benefits of gardening. The cost of some gardening supplies, such as seeds and compost, could continue to rise, but once you have the tools, wheelbarrow, maybe fences, etc., their cost is amortized over years of gardening. You thus escape most of the industrial elements contributing to food inflation. Meanwhile, the healthy effects of home-grown food will continue to appreciate in your body, mind, and soul. It’s a relatively low-cost, high-benefit investment in yourself when done properly, which is not difficult.

Independent of subsidies

Unlike farmers, who usually expect to be paid to adopt sustainable agriculture practices, ultra-local gardeners don’t require support from the government. True, community gardens can depend on subsidies or grants, at least to get started, but the home gardener doesn’t. The 50% of Russian food coming from household gardens on just 3% of the country’s agricultural land received zero help from the Russian government; no subsidies. In fact, historically the government often made things difficult for its gardeners, going as far as some despots who outright stole their bounty. No matter, the gardens have continued anyway, through all challenges, since before the czars.

I don’t know of any farm-based food system using sustainable ag practices that has shown the ability to provide food for scores of millions on a continuing basis, subsidies or not. But that’s what Russia’s system has done for a long time, although you’d never know it from reading accounts of sustainable ag programs around the world. Here in the U.S., we did show the ability to get started in that direction, when that 40% of the country’s vegetables were produced from 20 million gardens during WWII. Unfortunately, that initiative ended once the war was over and the government started pushing heavy industrial use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

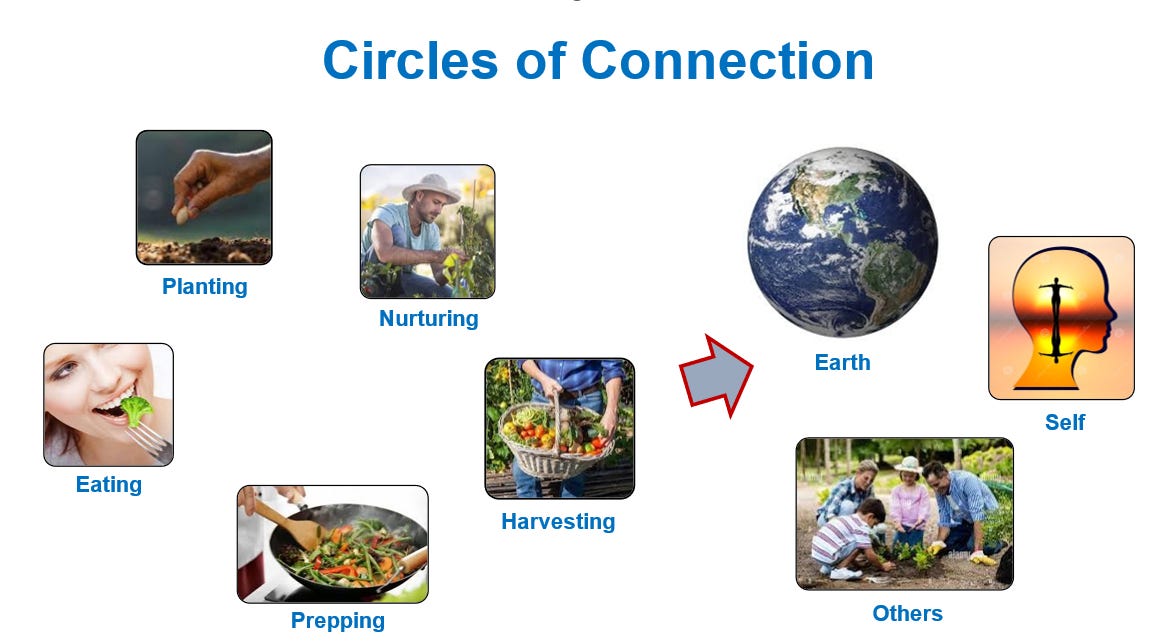

Well positioned to address the main industry problem

As mentioned in the previous post, ULFs—in their most useful version produced in self-sufficiency gardens—are the extreme opposites of the industrial food system’s biggest problem: UPFs. Most importantly, ultra-local foods provide ultra-healthy fare, as opposed to ultra-processed food (again, now 75% of our diet), which is linked to a wide range of unhealthy outcomes. In addition, ULFs also offer a benefit that even CSAs or farmer’s markets sourcing their goods from small, local, or regenerative ag farms can’t match: full-circle connections. Because even if you pick up that wonderful zucchini or tomato from a table at a farmers market, you didn’t plant, nurture, and harvest it yourself, thereby missing out on the first three steps of the full circle of gardening.

Further, you miss out on the enhanced second circle of connections to the earth, yourself, and others that result from completing the first circle on a continual basis. Those benefits don’t occur to most people, not even most gardeners, because they haven’t experienced the full sense of self-empowerment and deep satisfaction that comes from providing 1) a balanced diet 2) comprising entire meals that 3) they’ve grown themselves 4) over an extended period of time, whether it’s a day, a week, month, or even up to a year. You can’t be expected to miss what you haven’t yet tried out for yourself. Although you might be able to imagine it. Try it.

Friendly, easier to implement

Yes, the prospect of putting in a garden can be intimidating or off-putting to many people. But because it requires so much less of an investment of time, money, and effort than transitioning a farm from conventional to regenerative agriculture, it’s a much easier to imagine doing it. Going regenerative entails a far greater learning curve and financial risk to the average farmer, who already has the industrial deck stacked against him, than converting a few square feet of lawn into a luscious garden. And since most of the fruits of regenerative ag would presumably be fed into the industrial food chain, with many ending up in UPFs, there would be a much greater ROI at the collective health level for ULFs coming from self-sufficiency gardens.

Fast and feasible to ramp up

Ramping up those 20 million gardens during WWII was accomplished within a year of two, on short notice, with little training or prior experience. Today, with 41% of households already having a food garden of some kind, the basic infrastructure needed to transition to a self-sufficiency food system is already widely in place. All that’s needed, really, is to up the concept of a typical garden from where it is now to balanced-diet self-sufficiency—not a huge undertaking. Regenerative ag would require a far greater investment of time, money, energy, land procurement, and farmer training to ramp up enough regenerative ag farms to massively transition the country to a healthier food supply. To reiterate once again, conventional is converting to regenerative at the rate of only 1% of farmland per year. That’s commendable as far as it goes, but at that rate it would take generations to significantly magnify it.

Not too late to effectively address climate change

It’s precisely because self-sufficiency gardens can be relatively quickly scaled up that makes them so timely. In the face of accelerating climate change disasters, bird flu, Trump’s tariffs and removal of federal services to industrial agriculture—as well as other food system challenges like increasing costs of farm chemicals—we are ill-prepared for the near-term future of food. As you’ve seen above, it’s simply too late for regenerative ag to even try to meet the challenge; it just doesn’t have the needed inherent capacity to move quickly. By contrast, ULFs and a self-sufficiency garden food system are proven to be much more nimble, quick, and easy to leverage into significant volume on a massive scale. It’s the right tool to prepare for the daunting future of food security.

Strong, smart, capable

Perhaps the greatest advantage of this proposal is that it doesn’t require entering into or changing the industrial juggernaut in any way. That system will continue doing what it’s doing for as long as it can. So the solution is to go around it instead of depending on, joining, or fighting it. An ultra-local, full-circle, self-sufficiency system of food production would stand on its own. Yes, it will require businesses that help provide compost, mulch, gardening supplies, greenhouses, education, and—for the infirm—done-for-you gardening services. But those can be sourced outside of the industrial food system. They’re part of the gardening infrastructure that is already in place, although it would have to be expanded to service a garden system that could—like that other country does for its people—supply at least half of our food. Which by the way will provide many new jobs. The conclusion is clear: don’t try to change the existing system with a well-intended but not-nearly-enough tweak. Rather, build up a new one that makes the existing system no longer the only game in town.

This has been a lot to take in and digest, so I’ve summarized it in the following two tables. Review them, be informed, and stay tuned.

1Bless, A. 2023. “Regenerative agriculture” is all the rage—but it’s not going to fix our food system. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/regenerative-agriculture-is-all-the-rage-but-its-not-going-to-fix-our-food-system-203922

22015. The cost of organic food. A new Consumer Reports study reveals how much more you'll pay. Consumer Reports. https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/news/2015/03/cost-of-organic-food/index.htm#:~:text=We%20compared%20more%20than%20100,change%20based%20on%20weekly%20promotions

3Rawnsley, J. 2024. The rise of the carbon farmer. https://www.wired.com/story/carbon-farming-regenerative-agriculture/

4Kiss the Ground. 2020.

https://kissthegroundmovie.com

5How many farms are regenerative. 2025. Regenerative farmers of America. https://www.regenerativefarmersofamerica.com/regenerative-farm-near-me#:~:text=How%20many%20farms%20are%20regenerative,1.5%25%20is%20being%20farmed%20regeneratively.

6Toplensky, R. 2024. Sustainable Agriculture Gets a Push From Big Corporations. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/sustainable-agriculture-gets-a-push-from-big-corporations-55541180

7NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) 2025. U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/, DOI: 10.25921/stkw-7w73

8Hyman, M. 2020. Food fix. Yellow Kite.

9Sharashkin, L. 2008. The socioeconomic and cultural significance of food gardening in the Vladimir region of Russia. PhD dissertation, University of Missouri.

10Langelatto, G. 2014. What Are the Economic Costs and Benefits of Home Vegetable Gardens? Journal of Extension, Oregon State University. Vol.52, No.2. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2014april/rb5.php#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20home%20vegetable%20gardens,value%20realized%20by%20individual%20gardeners.