The Food System in Slow-Motion Freefall

Is the U.S. food system in danger?

The answer is yes, but it’s not about to completely collapse overnight—it’s more like a slow cascade. Yet it’s not too early to think about growing your own food, either, just for peace of mind in case groceries start to get scarce or expensive. Many lower-income people, especially those who depend on government assistance or food banks, have already reached that point. If you’re an influencer—that is, an information gate-keeper such as an editor, or a thought leader like Michael Pollan, or a government policy-maker—you may be more worried about the security of the country as a whole. Or perhaps you’re just a concerned observer who would like to do something to help.

Like what, for instance? Well, on the individual level, plant a starter self-sufficiency garden (more on how to do that in a later post). At the mass level, help galvanize a garden food system that would supply up to 50% of the nation’s food in the form of a healthy, balanced diet. This, of course, is what I’ve been pushing all along. I’m thinking primarily about the U.S., secondarily Canada and Europe, and then the rest of the world. I start with the U.S. because we run the world’s least efficient and most damaging version of industrial food, and for better or worse we lead by example. However, I don’t discount the possibility that some other country or region could get inspired enough—possibly out of sheer necessity—to leapfrog ahead of us. In fact, Russia has already reached the 50% mark, as I’ve noted many times. But no one is following their example. Yet.

The Global Food System in Turmoil

It’s not that major food watchers are oblivious to global food insecurity. The UN and other relief agencies like Oxfam beat the drums about it all the time, to no avail that goes much beyond emergency infusions of financial or food aid, or short-term, stop-gap business-as-usual fixes. But amping up the drums, 100 Nobel Prize Winners recently signed an open letter warning that BAU will not meet the food needs of an expected ten billion people by 2050. Not even close.

Some prominent thinkers believe that the global food system is all but certain to crash unless we do something truly drastic to prevent it (such as replacing real food with bacterial goo). Here are a couple examples of their reasoning1,2.

Others tiresomely advocate worn-out “action steps” they insist can, could, should, would, or “promise to” stave off starvation while now weaving in the challenge of climate change. Most of their proposed fixes—none of which marshal compelling evidence of effectiveness at massive scale under climate change duress—will be familiar to any global food system expert.

How the experts say we can feed the world

Increase the total output of crops and livestock.

This is the knee-jerk strategy of virtually all mainstream media pundits, and even—still (!)— many agronomists. Its go-to justification used to be the claimed success of the Green Revolution, which we now know causes more food, social, and environmental problems than it solves. Still, two billion more people by 2050—about 25% more than now—means we need to produce a lot more food by then. And that means—according to the prevailing narrative—greatly increasing yields with more chemicals and water, better financing, “smart” technology, and improved crop genetics. But since increasing yields over the last 70 years has not solved food problems, the only alternative is to clear 25% more land to further ramp up agriculture-as-usual. That, of course, would spike greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in ever-hotter weather—making it much harder for all the other prescriptions to work in most parts of the world. This is the “feeding the world without frying the world” conundrum2,3.

Shift from meat to plant-based foods and meat substitutes.

Oh, my, for how many decades now have the experts lectured that solving food insecurity means eating less meat and more plants? Yet look what’s happened: a prodigious net increase in global meat demand and production. In general, people just aren’t prepared to give up their meat. Meanwhile, ventures into plant- and/or fungi-based substitutes and lab-cultured meat have been mostly duds. I’ve even seen one idea, mentioned previously, to free us from farms by turning non-agricultural feedstock such as fossil fuels into edible—if not very tempting—synthetic food.4 Besides leading investors into financial dead-ends, the purveyors of such next-generation foods have missed emerging evidence that it’s the ultra-processing, more than harmful ingredients, that make them unhealthy. Food from lab dishes or petroleum? Not just ultra-, but hyper-processed foods (HPFs?). And as we’ve seen, ordinary UPFs are already on the ropes health-wise.

Reduce food loss and waste.

Again, the food authorities have harangued us for many years that if we could just eat instead of wasting 30-40% of the food the world produces, no one would go hungry (at least for the time being). But in spite of repeated waste-reduction initiatives here and there—imploring restaurants and grocery stores to give their unusable food to the needy, being careful to buy only what you eat, salvaging food otherwise lost at various points along food chains up to hundreds of miles long—the waste mess has not significantly improved. Habits all along the chain are evidently just too deeply entrenched to let go of, with or without shaming and blaming.

Shift to healthier agricultural production.

That is, healthier for both farmland and people. Principal among these is the now ever-hyped regenerative agriculture. In an earlier post I discussed eight reasons why, despite its superficially admirable features, it has no hope of succeeding at scale over the longer run. Then there’s “vertical” agriculture, in which vast greenhouses substitute tightly-packed walls of LED light bulbs for sunlight, safely out of the weather and not limited to the warmer growing seasons. But this approach only works for watery vegetables like lettuce, greens, tomatoes, and cucumbers—not calorie- and protein-rich items like corn, sweet potatoes, and dry shell beans. Those staples require the full sunlight that LEDs can’t match. You can’t live on water, fiber, vitamins, and minerals alone.

Stop diverting food to biofuels.

In the U.S., about 40% of corn and 40-46% of soybean oil goes to biofuels. Most cars in Brazil run on ethanol derived from sugarcane. And globally, food crops produce 810 calories a day per person that end up feeding cars and trucks instead of people. Nevertheless, again because of excessive waste and loss in the industrial food chain, diverting those fuel stocks back to food would make no more than a small dent in the global food supply. Besides, the food-to-fuel industry has no intention of loosening its grip on its heavily subsidized gravy train.

Adapt to climate change.

Actually, all of these proposals could be played as attempts to adapt to climate change. Yet a recent, massively comprehensive study—spanning 12,658 regions, and two-thirds of global crop calories—reported that six key staple crops will likely see a substantial production drop over the coming decades.5 Surprisingly, it also found that the areas least able to adapt to global warming will be not the poorest regions of the world but the bread baskets of the richest countries, such as the Midwest of the U.S. So perhaps our own food supply is in greater danger than we thought.

In addition, given the dependence of many countries on U.S. and a few other major ag exporters, this study not only tightens the amount of time we have to adapt, it also strongly suggests that we need to step outside of our deeply entrenched (read: industrial) mindset to see how best to adapt.

And others

Some prescriptions don’t fit neatly into these categories, such as ramping up relatively minor sources of global food like fish, and convincing African and some Asian women to have fewer babies. Others include addressing the rapidly accelerating demise of honeybees, upon which billions of dollars worth of crops depend for pollination, and fortifying nutritionally-depleted crops with vitamins or minerals.

Regardless of the fix, it all needs to be accomplished before increasing carbon emissions (due to no small degree to agriculture) render the industrial system so overheated it’s nonfunctional. Again, feed the world without frying it.

So what to do?

Overall, the elephant-in-the-room reason none of these proposals will work is that they all depend on fixing the industrial food system, as it’s widely held to be the only way to mass-produce food. Yet its gross inefficiency and outsize collateral damage, which the University of Oxford says destroys more value than it creates6, is itself the source of the problem. And even if the prescribed fixes could somehow be forced to work, they would need lengthy and massive campaigns to change entrenched habits and/or decades of research, development, and infrastructure scale-up.

The conclusion reached by the Nobel Prize winners, as well as Bendell, Monbiot, a growing number of food system experts, and the study mentioned above, is that without some drastic new (not tired old) approach, we simply cannot come even close to feeding two billion more people by 2050. And even if we did, we’d then be faced with far more mouths to feed over the subsequent 25 years.

Tellingly, the blinkered belief—still held by many—that tired old strategies could work rests on the following widely-held but invalid assumptions:

1. Only farms can produce significant amounts of food for the world.

This, as the production of half of Russia’s food by gardens has demonstrated, is the mother of all misapprehensions about food systems. Not surprisingly, it drives the next four assumptions, each building on the previous one:

a. The global food supply comes almost entirely from industrial production.

No, it doesn’t. The FAO held for years that only 30% of the global food supply was due to large-scale industrial efforts. Then two studies claimed it was more like 70%.6,7 However, not only did they ignore evidence of large amounts of alternative food sources, they also based their estimates on the assumption that 100% of industrial production is consumed. As we’ve seen, only about 5-15% of the U.S. material harvest makes it to the consumer’s fork, and the global average isn’t much better.

b. Agricultural production is largely equal to consumption.

No, it isn’t, as just noted. Yet you see the production-equals-consumption myth inferred just about everywhere in the popular press. It’s even still used in some food system analyses.

c. All adaptations in food production will consist of industrial tweaks.

Where else could they come from if all we had was the industrial model to feed the world? Yet, as the household garden model in Russia has shown, industrial is not all that we have.

d. Increasing yields is essential to reducing food insecurity.

No it isn’t, in large part because of the inability of increased yields to do the trick, as discussed above. But it’s also because when a much greater proportion of food production results in consumption, as with household gardens, it’s not necessary to make up for massive industrial loss and waste by pumping out equally massive yield increases.

The folly of basing food security on these invalid assumptions founders even further on the next two, equally flawed suppositions:

3. The pace of climate change won’t continue to accelerate substantially.

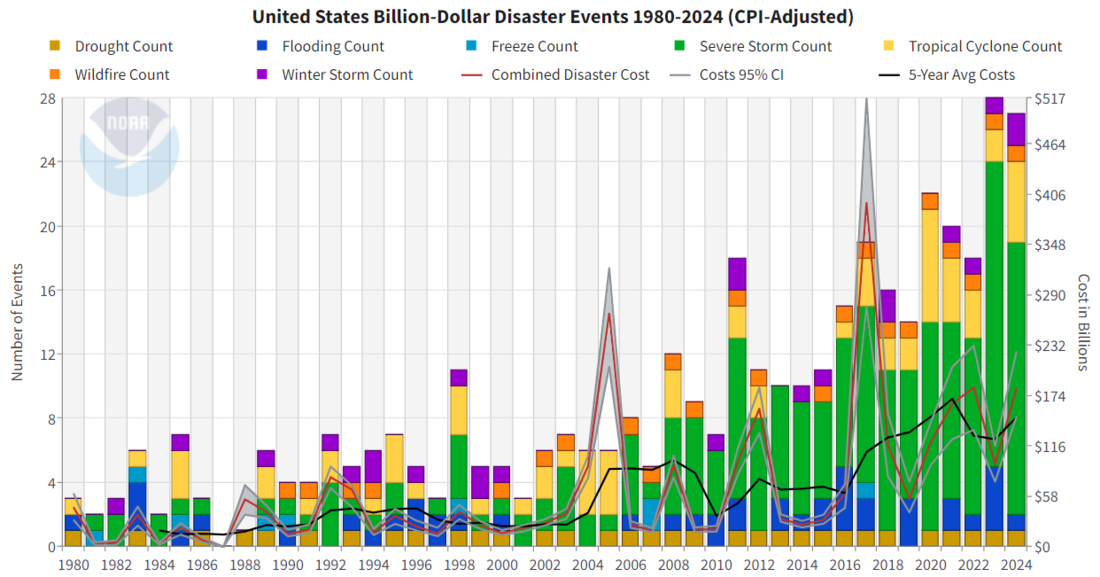

Even though the perils of climate change are now widely acknowledged, an unstated assumption persists that the pace and intensity of disasters won’t continue to get much worse. NOAA’s record of billion-dollar disaster events from 1980 to2024, however, indicates otherwise.8

4. We still have decades to develop and implement needed adaptations.

Many of the proposed fixes assume that we have 25 years or even much longer to step up massive attitude changes or infrastructure buildout needed to implement them. Given the sharply accelerating pace of climate change, we simply don’t have that time. Doubtful? Then do a thought experiment: logically extrapolate the end of the curve in the NOAA graphic from 2024 to an imaginary 2050 and you’ll see what I mean. At some point well before 2050, multi-billion-dollar disasters will overwhelm the government’s rescue capacity, likely preceded by disappearing insurance coverage, which is already beginning to happen in hurricane-prone Forida.

Overall, it’s a truly fatuous tower of cards, with the mother of all assumptions propping up the equally dubious children above it. The upshot is it just doesn’t make sense to try and beat a dead horse (i.e., fix the industrial food system), especially when climate change and other disruptors are so rapidly encroaching upon us. Any one of them, or maybe two or more acting together, is/are more than capable of tipping over the food system grocery cart long before the fixes could take effect.

The only solution that does makes sense is to build up a proven self-sufficiency garden food system based on solid premises. Because it’s far more efficient than the industrial system, it can easily feed two billion more people without pumping a monstrous new pulse of carbon into the atmosphere. In fact, because its food footprint is a small fraction of industrial’s, it will free up a lot of land for natural vegetation, which is more efficient at sequestering carbon than agricultural fields of any kind. At the same time, it will give the industrial system time to salvage what it can of itself, as it has no choice but to do in any case. As I’ve pointed out again and again, we’ll still need it to feed densely populated areas, at least for a while. Just don’t expect it to revamp itself enough to feed the world without frying it; it simply can’t. So stay tuned to see in more detail why gardens offer by far the best hope for food.

1Bendell, J. 2023. Breaking together – A freedom-loving response to collapse. Good Works.

2Monbiot, G. 2022. Biogenesis – Feeding the world without devouring the planet. Penguin Books.

3Grundwald, M. 2025. We are eating the Earth – The race to fix our food system and save our climate. Simon and Schuster.

4Davis, S.J., et al. 2024. Food without agriculture. Nature Sustainability. 7: 90-95.

5Hultgren, A. 2025. Impacts of climate change on global agriculture accounting for adaptation. 642, 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09085-w

6University of Oxford. Fixing the broken food system would unlock trillions of dollars in benefits, study finds. News and Events. https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2024-01-29-fixing-broken-food-system-would-unlock-trillions-dollars-benefits-study-finds#:~:text=Currently%2C%20our%20food%20systems%20destroy,to%20diet%2Drelated%20chronic%20disease.

6Riccariadi, et al., 2018. How much of the world's food do smallholders produce? ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325405959_How_much_of_the_world's_food_do_smallholders_produce

7Lowder, et al., 2021. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? World Development. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X2100067X

8Smith, A.B. 2025. 2024: An active year of U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. NOAA Climate.Gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2024-active-year-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters